William Kerrigan, author of Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard, and Hank Fincken, living history performer. cambridge, Ohio, April 2013.

Last year I had a unique opportunity as a scholar to share a double-bill with a professional actor. With the generous support of the Ohio Humanities Council, the public library in Cambridge, Ohio invited me to deliver a lecture on John “Appleseed” Chapman and to sign and sell copies of my recent book, Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard. After a brief intermission Hank Fincken took the stage in the character of Johnny Appleseed. For act three, Hank and I jointly answered questions from the audience. When the library first broached the idea of a Johnny Appleseed double-bill, I was both enchanted with the idea and a little bit intimidated. How would a lecture by an academic historian stand up when placed in conjunction with a compelling, dramatic, comic and lively first person performance delivered by an experienced actor who has mastered the skill of engaging diverse audiences across decades of experience? But I was also excited about the possibility of opening up a conversation about the ways we understand the past.

French and Indian War Re-enactor. Photo by Eric Gaston.

A lifetime ago in grad school, I spent warm summer days in a windowless, climate controlled concrete bunker called the library annex, poring over 19th century periodicals, researching my dissertation. About mid-July I needed to escape, and hopped in my car and drove north to Fort Michilimackinac in northern Michigan. There I stumbled across an encampment of French and Indian War re-enactors, and found myself in conversation with one. When I asked him how he came to be involved in re-enacting, he told me that he used to participate in history roundtables, where people got together to discuss books. But he finally concluded that “you don’t learn history in books, you learn it in your bones,” dropped out of the roundtable and took up re-enacting. When I asked him to explain this heresy he replied, “Well, when you sleep on the ground, you learn the ground is hard.”

In subsequent years I began taking undergraduate students on biennial Civil War study tours, and we always tried to include a Civil War encampment and battle re-enactment in those trips. The Civil War re-enactor subculture is quite distinctive, and compellingly examined in Tony Horwitz’ Confederates in the Attic. In my many interactions with re-enactors I have learned to appreciate that through these rituals they learn something meaningful about the sensory experience of the Civil War soldier, but I have encountered many whose understandings of the bigger picture—like the causes of the war—were highly dubious. Bones alone will not impart wisdom.

While re-enactors seek a connection with the past for their own use, living history performers like Hank Fincken and academic historians like myself interpret the past, seeking to convey knowledge to an audience. In conveying the story of John Chapman, Hank and I are each engaged in an act of interpretation, struggling to find the truth. Our interpretations of the man and the meaning of his life are not perfectly aligned, but I have found Hank’s Johnny Appleseed compelling and persuasive. Over the many years I spent researching the life of John Chapman, I saw many amateur actors, and a few professional ones, perform in the role of Johnny Appleseed. Most were pretty forgettable. The problem, it seemed to me, was the desire to portray John Chapman as a saint—a physical representation of pure goodness and a role model for children—one so perfect that they could not hope to emulate him. Not only did these Johnny Appleseeds not resemble any real person I had ever met, their performances put me to sleep. Hank’s Johnny Appleseed was quite different from the saintly ones. His Johnny was irascible, rascally, comic, mostly endearing but a bit off-putting—in other words thoroughly human.

The difference in our approaches is never more stark in the way we each answer this commonly asked question:

Did Johnny Appleseed really wear a tin pot on his head?

As an academic, my answer begins with written sources, and tends toward the verbose. I explain that while there are some accounts that mention a tin pot hat, others describe a vast array of interesting head-gear; that he may have worn a pot on his head once, or even occasionally, but it wasn’t his everyday head gear. For Hank (whose Johnny Appleseed does not don a pot), the answer is more direct, and something like this:

“if you believe Chapman wore a pot on his head, I encourage you to go home today and put a pot on your own. Wear it for a few days, and let me know if you still believe a pot can perform as practical headwear.”

Despite our different ways of answering that question, our approaches are not completely different. What makes Hank Fincken a credible living history performer is that he understands that essential knowledge comes not just from your bones, but also from texts. He has read all of the biographies of John Chapman, as well as the most important primary sources on his life. He has spent endless hours mulling over these materials and crafting them into scripts. Likewise, I also occasionally took a “bones” approach to the

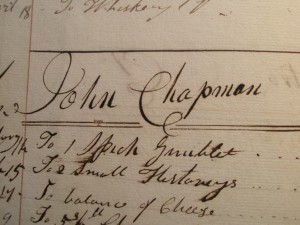

life of John Chapman. On Northwestern Pennsylvania’s Allegheny Plateau, I stood barefoot on the smooth gray stones in the Brokenstraw Creek, knee-deep in its chilly spring waters, near the location of Chapman’s first creekside apple-tree nursery. I cannot articulate in any scholarly way how doing this helped me understand John Chapman, but I certainly felt as if it did. Hours later, in the reading room of the Warren County Historical Society, holding in cotton-gloved hands a crumbling dry goods store ledger where John Chapman bought an assortment of items, I felt that once again. Even an archive can yield some “bone-knowledge,” and scholars would be wise to consider its value.

William Kerrigan is Cole Professor of American History at Muskingum University in New Concord, Ohio, and author of Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard (Johns Hopkins, 2012).

You must be logged in to post a comment.