The focus of American Orchard, according to its subtitle, is to offer “historical perspectives on food, farming, and landscape.” Those who know me understand that trees, and especially apple trees, are the focus of much of my research. But as a professor at a small liberal arts college I teach broadly, and the American Civil War and its memory are both a personal interest and a focus of much of my teaching. I occasionally find opportunities where my interests in trees and the Civil War intersect, and perhaps some of you have read my entries on efforts to restore battlefield orchards, at places like Gettysburg, Fredericksburg, and Antietam, and perhaps also my ramblings on Johnny Appleseed and Stonewall Jackson in American memory. I have found an opportunity to explore that intersection of interests once again.

This summer I have been working with an exceptional undergraduate student who is completing a research project on historical memory of the Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery in Columbus, Ohio. As the nation struggles to reconsider how the Civil War should be remembered in the wake of horrible events in Charleston, South Carolina, my student could not have fallen upon a more timely topic, and I look forward to what promises to be a unique and significant contribution to scholarship on Civil War Memory.

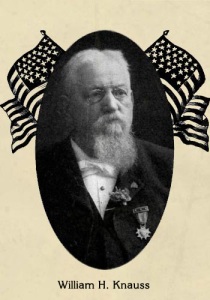

The Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery in the Hilltop neighborhood of Columbus, Ohio holds the remains of 2260 Confederate soldiers, most of whom died in the Camp Chase prisoner of war camp during the Civil War. For many years after the war, this Confederate Cemetery in the heart of a Union state was largely neglected and overgrown. In the 1890s a local Union veteran made it his mission to restore the Camp Chase cemetery, so that it might be a suitable place to remember the Confederate soldiers buried there. William Knauss had been wounded at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862. Years later he made a visit to the city to revisit the site of this terrible battle, and a former Confederate soldier, also wounded at Fredericksburg, gave him a tour of the battlefield. The two men found “common ground” in a quite literal sense while walking the landscape of their past suffering, and they made a pact that whenever either of them came across the untended or forgotten graves of soldiers on the other side of this conflict in their home states they would do what they could to restore and protect them. Restoring Camp Chase cemetery was William Knauss’ effort to honor that pact. He had a new stone wall erected around the cemetery, improved the gravesites, and commissioned a granite arch to be installed in the center of the cemetery. The arch was engraved with the word “Americans,” and topped with a common Confederate soldier.

The Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery in the Hilltop neighborhood of Columbus, Ohio holds the remains of 2260 Confederate soldiers, most of whom died in the Camp Chase prisoner of war camp during the Civil War. For many years after the war, this Confederate Cemetery in the heart of a Union state was largely neglected and overgrown. In the 1890s a local Union veteran made it his mission to restore the Camp Chase cemetery, so that it might be a suitable place to remember the Confederate soldiers buried there. William Knauss had been wounded at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862. Years later he made a visit to the city to revisit the site of this terrible battle, and a former Confederate soldier, also wounded at Fredericksburg, gave him a tour of the battlefield. The two men found “common ground” in a quite literal sense while walking the landscape of their past suffering, and they made a pact that whenever either of them came across the untended or forgotten graves of soldiers on the other side of this conflict in their home states they would do what they could to restore and protect them. Restoring Camp Chase cemetery was William Knauss’ effort to honor that pact. He had a new stone wall erected around the cemetery, improved the gravesites, and commissioned a granite arch to be installed in the center of the cemetery. The arch was engraved with the word “Americans,” and topped with a common Confederate soldier.

And then William Knauss did one more thing. He wrote letters to Confederate veterans organizations in every southern state, and asked if they would send small native saplings to him, so that they might be planted amidst the graves of the Confederate dead, who may not have made it home, but might now rest beneath the shade of southern trees. Many veterans organizations responded, and more than a century later, about a dozen mature trees provide shade for the Confederate dead. Some of them are not these original trees, but many of them almost certainly are. Today a Walnut tree, several Oaks, a Tulip Poplar, a wide-spreading Sweet Gum, and a majestic old Catalpa cool the ground where these men lay.

Almost every year since William Knauss restored the cemetery one organization or another has held a ceremony to remember the men buried there. For much of the twentieth century, a local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy organized the ceremony; since 1995 it has fallen to the volunteers of the Hilltop Historical Society. A few weeks ago my student and I attended the annual ceremony conducted by the Hilltop Historical Society to remember the men buried there. The ceremony was beautifully done, and the main speaker struck just the right tone. He told the stories of three of the men buried there, of their horrible suffering, and their tragic end. We remember these soldiers, he suggested, because they were among those who even after death, were unable to return home. There was no Lost Cause mythology in the ceremony, no effort to explain away slavery as the cause of secession, nor, thankfully, to portray slavery as a benign institution.

A Union Regimental Band plays under the shade of a mature Sweet Gum tree. Confederate battle flags decorate the graves of the southern dead.

Still there was one aspect of the ceremony that gave me pause, and that was the planting of Confederate battle flags in front of the graves of the Confederate dead. The flags seemed even more problematic in the shadow of an arch that declared these men “Americans,” and also knowing that when my student and I had visited the cemetery just a few weeks earlier, just after Memorial Day, we found that a local Girl Scout troop had decorated each grave with an American flag. Could these men be both agents of a political movement that sought the dissolution of the nation, AND Americans? Lincoln and the North went to war because they believed these men to be Americans, deluded by demagogic leaders of the Slave Power, but Americans nonetheless. Yet so many of the champions of the Confederacy, during the war and after, argued that their right to separation was built in large part on the grounds that they were “Southrons,” a culturally distinct people from northerners. Would these men have identified themselves as “Americans” in 1864 and 1865, the year so many of them perished from hunger, cold, and disease? It is not an easy question to answer.

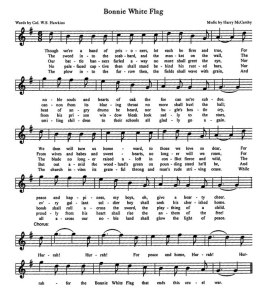

Many had marched off to war years earlier singing “The Bonnie Blue Flag,” a song that declared they were fighting for their “property” and “For Southern Rights, Hurrah!” Yet late in the war, a southern prisoner at Camp Chase rewrote the popular song, changing the title to “The Bonnie White Flag,” the chorus to “Hurrah, Hurrah, for peace and home hurrah!” and including the language “Our battle banners furled away no more shall greet the eye, nor beat of angry drums be heard, nor bugle’s hostile cry.” Many of the men buried in the Camp Chase cemetery were likely among the first to sing this new anthem to peace and home. There is reason to question whether these dead would have welcomed the planting of the Confederate battle flag upon their graves. So how should we remember these men, who suffered and died so tragically, and so far from the homes to which they hoped to return? I can think of no better monuments to their memory than the majestic southern trees that now shade their graves, trees which in some small way brought “peace and home” to them.

Many had marched off to war years earlier singing “The Bonnie Blue Flag,” a song that declared they were fighting for their “property” and “For Southern Rights, Hurrah!” Yet late in the war, a southern prisoner at Camp Chase rewrote the popular song, changing the title to “The Bonnie White Flag,” the chorus to “Hurrah, Hurrah, for peace and home hurrah!” and including the language “Our battle banners furled away no more shall greet the eye, nor beat of angry drums be heard, nor bugle’s hostile cry.” Many of the men buried in the Camp Chase cemetery were likely among the first to sing this new anthem to peace and home. There is reason to question whether these dead would have welcomed the planting of the Confederate battle flag upon their graves. So how should we remember these men, who suffered and died so tragically, and so far from the homes to which they hoped to return? I can think of no better monuments to their memory than the majestic southern trees that now shade their graves, trees which in some small way brought “peace and home” to them.

You must be logged in to post a comment.