Between May 13 and May 23, 2013, I co-taught a study tour of Civil War battlefields with a colleague. While this was the sixth time I have offered this study tour for undergraduate students, I decided at the outset that I would use this opportunity to gather information about orchards on Civil War battlefields. I was aware of the “famous” peach orchard where many men died on the field at Gettysburg, and was aware of a few other references to battlefield orchards, but was surprised at the abundance of information I uncovered on the eleven day trip. This is the first in a series of blog posts on battlefield orchards.

Joseph Sherfy purchased land along the Emmitsburg Road, south of the town of Gettysburg, in 1842. Sherfy was a striver, and decades later his obituary declared that “he made out of sterile acres a most productive farm [and] deservedly stood in the front rank of intelligent and successful agriculturists.” Planting much of his land in peach trees, by the eve of the Civil War Joseph Sherfy’s peaches, which he sold fresh, dried, and canned, were locally famous, and his orchard appeared on an 1858 map of Adams county. The business supported Joseph, his wife Mary, and their six children.

When the Union army reached Gettysburg on the first of July 1863, Joseph Sherfy and his family were ready to help, providing water and bread to thirsty and hungry soldiers. The next day they were forced to evacuate their home, and did not return until the battle was over.

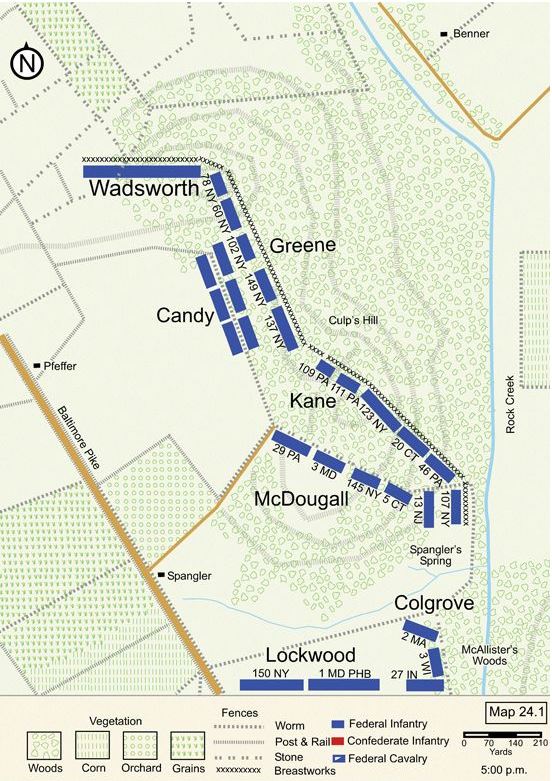

The vulnerable Union salient in Jospeh Sherfy’s Peach Orchard. From Bradley Gotffried’s Maps of Gettysburg

On days two and three of the battle, the Sherfy farm was in the midst of the conflict. A decision made by Union General Dan Sickles, against the orders of his commanding officer, ensured that Joseph Sherfy’s Peach Orchard would never be forgotten. Ordered to hold his men in a line that extended south of the town of Gettysburg to a hill called Little Round Top, Sickles’ decided instead to move his men forward to another spot of high ground in the middle of Sherfy’s orchard, a position he believed would be more defensible. By doing so, Sickles created a sharp bend in the line, a vulnerable “salient,” in the language of war, which could be attacked by the Confederate army from two sides. By the time Commanding General Meade realized what Sickles had done, easy retreat was not possible, and the soldiers in Sherfy’s Peach Orchard faced withering fire for several hours before those not killed were able to retreat. The fighting in and around the peach orchard salient is remembered as among the fiercest of the three day battle.

One of the few surviving images of the original Sherfy orchard, in William A. Frassanito, Gettysburg, Then and Now: Touring the Battlefield with Old Photos, 1865-1889.

What the Sherfy’s found when they returned to their home after the battle surely disheartened them. Their barn had been burnt to the ground, the exterior of their home was riddled with bullets, and the interior had been ransacked by Confederate soldiers. The soils in the orchard and elsewhere on the farm had been hastily dug up, with the corpses of soldiers buried wherever they had fallen, while forty-eight dead horses remained strewn about the orchard, swelling and decomposing in the summer heat. The Sherfy’s estimated their losses as $2500, but like most residents of the village, were awarded little or no compensation from the government.

Yet the peach trees in the orchard where so many men and beasts fell, rattled by canister and rifle fire, mostly survived. In the ensuing years, Joseph Sherfy’s peach orchard became a popular stop with returning veterans and curious visitors. Veterans shared their stories with the Sherfy’s and Mary Sherfy collected pictures of these men, displaying them on a wall in her home. Veterans of the battle, as well as tourists, were eager to view and touch a large cherry tree which stood alongside the Sherfy home, which had a 12 pound ball lodged deep within its trunk. “Soldiers and veterans saw trees (and their fragments) . . . as objects that provided access to the past, a vital link to the landscape of war they had created,” Mary Kate Nelson reminds us in Ruin Nation, her fascinating study of the war’s aftermath. Before they departed, both veteran and tourist to the Sherfy farm took away with them a souvenir of another sort–canned or dried peaches from the Sherfy’s surviving orchard.

Joseph Sherfy died in 1881, but his famous peach orchard survived him, and drew more visitors with each passing year. Just when and why the Sherfy orchards was uprooted I do not yet know. But for decades, the land remembered for the bloody fighting at “the peach orchard,” contained no peach trees at all.

The battle of Gettysburg was waged on the many family farms which surrounded the village, and most of these farms had orchards in 1863. The Sherfy’s peach orchard is the most remembered of these, but all across the battlefield, soldiers sought shelter from unrelenting fire beneath the trunks of fruit trees. In recent years the National Parks Service has begun an effort to restore many of its preserved battlefields to their condition on the eve of the battles fought there. In line with those efforts, the NPS has

T-shirts, peach taffy, and aprons, adorned with the Sherfy Peach Orchard logo, are now for sale at the Gettysburg Visitors Center.

partnered with local volunteer organizations to replant and maintain many of the fruit orchards which dotted the landscape of war. Gettysburg National Battlefield Park has perhaps done more than any other battlefield, and today dozens of young orchards are rising out of Gettysburg’s soils. New orchards also appear on the Trostle and Rose farms, adjacent to the Sherfy’s Emmitsburg Road farm. Many of the Confederate soldiers who assaulted Sherfy’s Peach Orchard did so from the Rose Farm’s apple orchard, which witnessed destruction as bad or worse than that inflicted upon the Sherfy Orchard. One early postwar visitor to the Rose farm declared that “No one farm on all the widely extended battlefield probably drank as much blood as did the Rose farm.”

William Kerrigan is the Cole Distinguished Professor of American History at Muskingum University in New Concord, Ohio and the author of Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard. He is currently working on orchards in American History. Other posts in this series on Civil War Battlefield Orchards include:

Orchards and Slavery on the Rappahannock

The Perils and Promise of Restoring Battlefield Orchards

Johnny Appleseed and Stonewall Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley

You must be logged in to post a comment.