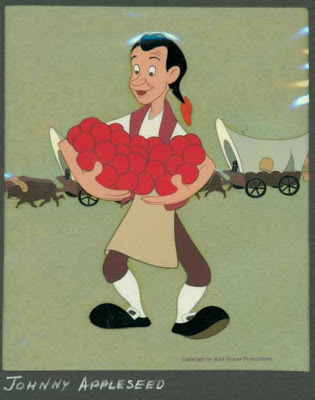

Johnny Appleseed’s Bible features prominently in the Disney version of the story, from the 1948 animated feature Melody Time.

John Chapman earned the nickname “Johnny Appleseed” during his lifetime, and people started sharing stories about the eccentric apple tree planter in the Ohio and Indiana communities where he spent much of his life long before he died in 1845. But Johnny Appleseed did not emerge as a figure in the American national origin story until the 1870s. In the late 19th century and throughout the first half of the twentieth century, most of the promoters of the Johnny Appleseed legend were social reformers, some of a socialist bent, who celebrated Johnny Appleseed’s efforts to promote a common social good by providing apple trees available to all. After World War II, the range of acceptable national myth narratives narrowed considerably. As the United States increasingly defined itself against Soviet communism, interpretations of Johnny Appleseed

Disney made Appleseed part of its team of early American superheroes, alongside Paul Bunyan, John Henry and others.

reflected this change. When Disney released an animated version of the Johnny Appleseed story in 1948, John’s faith in God was front and center. The narrator stated that three other great nation builders had their distinctive tools in their mission— Paul Bunyan had his axe, John Henry his hammer, and Davy Crockett his rifle— but Johnny Appleseed’s tools were his bag of apple seeds and his Holy Bible. The cartoon opens with a young Johnny singing a Disney-created song that has come to be known as “The Johnny Appleseed Grace,” and many believe it was actually written by Chapman.

And so I thank the Lord

For giving me the things I need

The sun and rain and the apple seed

Yes He’s been good to me

The Johnny Appleseed story told by Disney is a near perfect sermon on postwar American values. Faith in God and the ability of the individual to make a difference in history are the central themes. Johnny celebrates American freedom, singing, “Here I am ’neath the blue blue sky, doing as I please,” thanking God for that freedom. Soon his attention is drawn to a long train of Conestoga wagons pushing west, each containing a pioneer family. The wagon train has its own song celebrating American individualism:

The Johnny Appleseed story told by Disney is a near perfect sermon on postwar American values. Faith in God and the ability of the individual to make a difference in history are the central themes. Johnny celebrates American freedom, singing, “Here I am ’neath the blue blue sky, doing as I please,” thanking God for that freedom. Soon his attention is drawn to a long train of Conestoga wagons pushing west, each containing a pioneer family. The wagon train has its own song celebrating American individualism:

Out to the great unknown

Get on a wagon rolling west

Where you’ll be left alone.

The rivers may be wide

The mountains may be tall

But nothing stops the pioneer

we’re trailblazers all.

While John longs to join them, he believes he cannot— that he is too weak and too small,

The diminutive Johnny goes west without a gun, but in the Disney version, this is a result of his poverty and small size. No pacifist, he dreams of emulated the gun-toting frontiersman.

and does not own the gear he needs. Johnny’s “private guardian angel,” sent down from heaven, convinces him that all he needs is his faith, his Bible, and his apple seeds. Johnny sets out through a rugged wilderness, “a little man all alone, without no knife, without no gun,” but to avoid the impression that Johnny is a pacifist, Disney included a scene where he imagines he is shouldering a rifle like the ones he saw the men on the Conestoga wagons hold, and another where he picks up a stick from the woods, and pretends to aim and shoot with it.

The creatures of the wild forest Johnny Appleseed will transform into an ordered orchard embrace him as a friend.

Notably, the Indian makes only a minor appearance in Disney’s Johnny Appleseed. Instead, Johnny Appleseed works to win over the trust of the forests animals, convincing them, by his kindness, of the benign nature of his mission to transform the wilderness. The Disney story ends with an image of an aged Johnny Appleseed atop a ridge, his shadow stretching across a transformed landscape of fields and orchards:

This little man, he throwed his shadow clear across the land, across a hundred thousand miles square and in that shadow everywhere you’ll find he left his blessings three love and faith and the apple tree.

This little man, he throwed his shadow clear across the land, across a hundred thousand miles square and in that shadow everywhere you’ll find he left his blessings three love and faith and the apple tree.

Despite the story’s celebration of individualism, Disney’s Johnny Appleseed stopped short of praising difference in favor of conformity. Johnny Appleseed was a generic Christian in the story, not an apostle of unconventional Swedenborgianism. Johnny Appleseed could be an eccentric in postwar America, but the boundaries of that difference were increasingly constrained in a culture that valued conformity even as it professed to celebrate the power of the free individual.

You can view the entire Johnny Appleseed animated short here:

You must be logged in to post a comment.