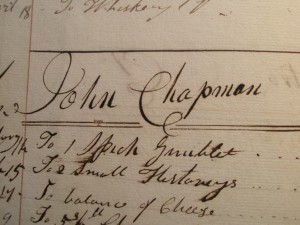

One of the many issues I explored in Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard was the question of John Chapman’s alleged vegetarianism. While I discovered some evidence that Chapman was not a vegetarian in his earlier years, he probably adopted a vegetarian diet later in life. In my efforts to contextualize Chapman’s alleged abstention from animal flesh, and speculate on its origins, I found an intriguing connection between Chapman’s religious disposition towards Swedenborgianism and the origins of American vegetarianism. For more on Chapman’s Swedenborgian religious beliefs read chapter four of Johnny Appleseed, or this blog post.

One of the many issues I explored in Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard was the question of John Chapman’s alleged vegetarianism. While I discovered some evidence that Chapman was not a vegetarian in his earlier years, he probably adopted a vegetarian diet later in life. In my efforts to contextualize Chapman’s alleged abstention from animal flesh, and speculate on its origins, I found an intriguing connection between Chapman’s religious disposition towards Swedenborgianism and the origins of American vegetarianism. For more on Chapman’s Swedenborgian religious beliefs read chapter four of Johnny Appleseed, or this blog post.

While Emanuel Swedenborg did not call for believers to adopt a vegetarian diet, he did portray the move toward a meat-centered diet as a symbol of man’s fall from paradise. Genesis 1:29-30 appears to endorse the idea that plants, not animals were God’s chosen food for man. Swedenborg argued that with man’s expulsion from the Garden, “man became cruel, like wild beasts, yea more cruel, first they began to kill animals and eat their flesh.” But Swedenborg did not conclude that God intended for man to abandon meat-eating. As post-Edenic man had developed a cruel nature, meat-eating was part of their fallen state, and therefore permitted.

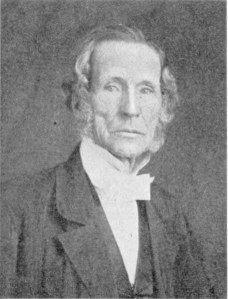

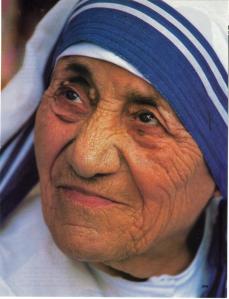

William Metcalfe, leader of the Philadelphia Bible Christians and advocate of abstinence from animal flesh.

Swedenborg’s writings on meat-eating nonetheless inspired some of the early English Swedenborgians to embrace a vegetarian diet. This splinter group of Swedenborgians came to be known as the Bible Christians, and they migrated to Philadelphia, a city that already had an active group of meat-eating Swedenborgians, in 1817. Over time, the Bible Christians dispensed with their Swedenborgian identity, and abstinence from both animal flesh and alcohol became their defining creed.

I of course was eager to determine whether Chapman’s probable shift to vegetarianism late in life was inspired by his reading of Bible Christian literature. It was impossible for me to establish any direct connection, but we know that Chapman was a voracious reader, and especially attracted to books and pamphlets on religious subjects. Furthermore, the Swedenborgian literature he freely distributed on the Ohio frontier he acquired from Philadelphia Swedenborgians. Chapman may have independently settled on a vegetarian diet after reading Swedenborg’s explanation of man’s fall.

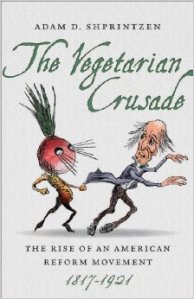

Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard was late in the production stages when I learned that historian Adam Schprintzen was completing The Vegetarian Crusade: The Rise of an American Reform Movement, 1817-1921. In that book, Schprintzen identifies the Philadelphia Bible Christians as the progenitors of a proto-vegetarian movement in the United States. I reached out to Dr. Schprintzen and he eagerly answered my questions about the Bible Christians and their connection to the Swedenborgian movement. When the Vegetarian Crusade was published, I immediately ordered a copy and read it.

Johnny Appleseed and the American Orchard was late in the production stages when I learned that historian Adam Schprintzen was completing The Vegetarian Crusade: The Rise of an American Reform Movement, 1817-1921. In that book, Schprintzen identifies the Philadelphia Bible Christians as the progenitors of a proto-vegetarian movement in the United States. I reached out to Dr. Schprintzen and he eagerly answered my questions about the Bible Christians and their connection to the Swedenborgian movement. When the Vegetarian Crusade was published, I immediately ordered a copy and read it.

The Vegetarian Crusade is an important book, and does an excellent job explaining the origins of American vegetarianism and its evolution across its first century. It should be on the bookshelf of every scholar of antebellum American history. Schprintzen sets the early movement in the context of antebellum reform. Early advocates of abstinence from meat, like all reformers of the era, understood their actions as part of a greater movement to improve society, to cleanse it from its sins, and for some, to help usher in Christ’s millennium. They drew connections between their movement and other reforms–non-violence, anti-slavery, women’s equality, and health to name just a few. Schprintzen does an excellent job explaining these connections in the years before the Civil War and in helping us understand the beliefs of these proto-vegetarians.

But that is just the first part of the Vegetarian Crusade. Schprintzen offers his readers much more that that, mapping out a clear and persuasive narrative explaining how we get from this antebellum proto-vegetarians to modern vegetarianism. That narrative introduces us to nationally-famous health reformer Sylvester Graham, a campaigner against white bread and advocate of a high fiber but bland and meatless diet, the emergence of the American Vegetarian Society in 1850, and explains how the Civil War and the post-war commercialization of a vegetarian diet by John Harvey Kellogg and others in the late 19th and early 20th century. It has been my intention to write a thorough review of Vegetarian Crusade and post it on this blog. Perhaps I will eventually find the time to give this excellent book the thorough review it deserves, but in the meantime, I’d like to point you to a place where you can learn more.

This week podcaster Liz Covart released an episode of her Ben Franklin’s World podcast that is a conversation with Adam Schprintzen, author of The Vegetarian Crusade. If you are not familiar with the Ben Franklin’s World podcast, now is the time subscribe and start listening. Every week Covart interviews an author of a recent book on Early American History. These are extended and lively conversations about important books. I can’t think of a better way to quickly get yourself caught up with the most important new scholarship on Early American History than listening to Ben Franklin’s World. Covart’s conversation with Adam Schprintzen is the 44th interview to appear on Ben Franklin’s World in just the first year of the podcast. Ben Franklin’s World just surpassed a quarter million downloads, and has been picked up by Spotify as well. Start listening to it now so you can say, “I was listening to BFW back when only the coolest people knew about it.”

This week podcaster Liz Covart released an episode of her Ben Franklin’s World podcast that is a conversation with Adam Schprintzen, author of The Vegetarian Crusade. If you are not familiar with the Ben Franklin’s World podcast, now is the time subscribe and start listening. Every week Covart interviews an author of a recent book on Early American History. These are extended and lively conversations about important books. I can’t think of a better way to quickly get yourself caught up with the most important new scholarship on Early American History than listening to Ben Franklin’s World. Covart’s conversation with Adam Schprintzen is the 44th interview to appear on Ben Franklin’s World in just the first year of the podcast. Ben Franklin’s World just surpassed a quarter million downloads, and has been picked up by Spotify as well. Start listening to it now so you can say, “I was listening to BFW back when only the coolest people knew about it.”

So pick up a copy of Adam Schprintzen’s Vegetarian Crusade and subscribe to Ben Franklin’s World podcast today. You won’t regret it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.